Rio Carnival History

Carnival celebrations happen all around the world, from Italy to France to India, England, Greece, Hungary, Russia, Haiti, Jamaica, and the Canary Islands — just to name a few. Of all the Carnivals taking place worldwide, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the Carnival in Rio de Janeiro is by far the largest! This article takes you through the fascinating history of Rio Carnival, starting in Europe before the dawn of Christianity and tracing its routes to the New World.

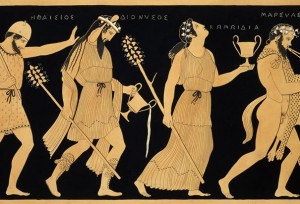

While today Carnival is a predominantly Catholic tradition, its history can be traced back to the pagan celebrations of pre-Christian times. Just because they are now considered ancient, that doesn’t mean that our ancestors didn’t enjoy a good party! Carnival has its roots in an era prior to the discovery of the New World, in which the ancient Greeks and Romans annually celebrated the coming of spring. The Greeks dedicated the festivities to Dionysus, the god of wine; the Romans adapted them with feasts in honor of Baccus, called Bacchanalia; and to Saturn with Saturnalia, in which slaves and their masters traded clothes in a day of intoxication and celebration.

For a long time, the Carnival of Venice was the biggest and most famous Carnival in the world. In order to maintain some semblance of control over the people during these festivals and parties in which people would wear masks and dance in the streets, the Church decided to adopt them as their own and sanctioned them. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church reshaped the pagan celebration of Saturnalia and turned it into a festival leading up to Ash Wednesday.

After Italy, the traditions of Carnival spread all across the Catholic nations of Europe, first making their way to Spain, Portugal, and France. From France, the Carnival spread to the Rhineland of Germany, and eventually to New France in North America. From Spain and Portugal, the traditions were brought with the Catholic colonists to the Caribbean and Latin America.

When the first explorers landed in the New World, these traditions continued as more and more settlers from Portugal arrived in what is now Brazil.

When the first explorers landed in the New World, these traditions continued as more and more settlers from Portugal arrived in what is now Brazil.

Historians trace the first records of Carnival in Rio to the year 1723. Back then, Carnival represented a short period of time in which the rigid traditions of distinct and inflexible class roles and status were completely flipped on their heads. One manner in which this was displayed was by the elite class would don the clothing of the lower class, and the lower class would wear the garments of royalty, allowing for a chance to confidently mingle with anybody.

Everyone in the city would parade and dance in the streets, providing a rare period of equality and unity. Today, the tradition of cross-dressing continues to be a vibrant aspect of Carnival and the tradition of relaxing societal norms prevails, as drag queens are a prevalent part of Carnival culture.

If Carnival wasn’t already a crazy event, imagine combining it with the exuberance of a Royal wedding. 1786 was one of the most historic Carnival celebrations to date as the festivities occurred simultaneously alongside the celebrations of the marriage between King Dom João IV with Princess Carlota Joaquina of Spain. The Rio Carnival of 1786 is marked in history books as wildest and most debaucherous party to date.

The Portuguese brought the party to Rio de Janeiro, but the French brought their balls. While the Portuguese are credited with bringing the concept of Carnival, or “celebration” to Rio, in the mid 19th century, the tradition of throwing elaborate balls was brought by bourgeoisie immigrants from Paris.

The first known masquerade ball happened in 1840 in Largo Rocio at Hotel Italia. The cost of admission included a full meal was two thousand réis, which excluded the lower classes making the balls an elite event. Today there is a Rio Carnival Ball for everyone and anyone!

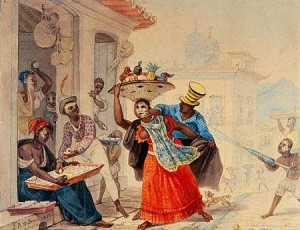

Some Rio Carnival traditions have survived over the years, but some didn’t quite make the cut. Portuguese settlers from the islands of Açores, Madeira and Cabo Verde introduced a tradition called Entrudo. Entrudo was an activity in which everyone would flock to the streets and the goal was to get everyone soaking wet by pouring water from buckets, throwing limes, or flinging mud.

With class and status unimportant during these times of festivities, nobody was excluded and everyone was a potential target. Though in 1855 a woman was reportedly jailed for slinging a lime at the bodyguards of the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro I; consequently, Entrudo was banned in 1855 because officials were uncomfortable with the lack of restraint.

By no means was the abolition of Entrudo the end of the party. 1855 was a big year, representing the introduction of Grandes Sociedades (Grand Societies), which was a highly organized parade that proved to be immensely successful — even the Emperor was spotted at the event. Comprised of a group of approximately 80 members of the aristocratic class, Grand Societies paraded down the streets playing music, and were the first to parade in ornate costumes and use props such as flowers.

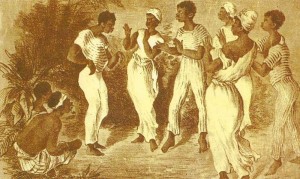

Like it is today, Carnival was a time where people from all walks of life come together as one. After Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822, slavery became a key part of the Brazilian economy. In fact, at the time Brazil was known as Little Africa and controlled around 35% of all slaves in the world. It’s hard to imagine, but keeping with the tradition of equality and unity for all during the Carnival festivities, slaves were welcomed in the Carnival celebrations and took advantage of these three days of freedom, becoming among the most active participants in the parade.

Like it is today, Carnival was a time where people from all walks of life come together as one. After Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822, slavery became a key part of the Brazilian economy. In fact, at the time Brazil was known as Little Africa and controlled around 35% of all slaves in the world. It’s hard to imagine, but keeping with the tradition of equality and unity for all during the Carnival festivities, slaves were welcomed in the Carnival celebrations and took advantage of these three days of freedom, becoming among the most active participants in the parade.

Today, the traditions of Carnival are significantly influenced by African culture. What’s more, the poverty-stricken black communities of Rio de Janeiro’s slums are still perhaps the most active participants in Carnaval preparations — and arguably, the Carnival celebrations means the most to them.

Samba music is the fire that energizes and keeps Carnival going with liveliness and enthusiasm. Since its birth, the sounds of the samba have stood as a cornerstone of Brazilian national identity and as a cornerstone of Carnival traditions. Over time, samba music developed in the city of Rio as a blending together of traditional African music with Brazilian dances and songs (like the polka, xote, maxixe, and the lundu), to create its own unique genre.

Samba music is the fire that energizes and keeps Carnival going with liveliness and enthusiasm. Since its birth, the sounds of the samba have stood as a cornerstone of Brazilian national identity and as a cornerstone of Carnival traditions. Over time, samba music developed in the city of Rio as a blending together of traditional African music with Brazilian dances and songs (like the polka, xote, maxixe, and the lundu), to create its own unique genre.

A bahian woman named Tia Ciata, born Hilaria Batista de Almeida in 1854, is credited with the birth of samba. She frequently played host to meetings in her living room, and would entertain her guests with live music. In the back lot of her house musicians would play drums and handclaps, and guests would perform a ritual dance called Candomble.

One day, when the music played by the musicians in her living room synched with the beat of the Candomble, the first samba song, titled Pelo Telefone, came into existence. African religious practices were banned in Rio in favor of Catholicism — and since it is heavily influenced by African music, culture, and religious traditions, for a long period of time samba music was not tolerated by members of Rio’s ruling aristocracy.

In the mid 19th century, José Nogueira de Azevedo, a Portuguese shoemaker, made a significant contribution to Carnival called Zé Pereira. Zé Pereira is the term used to reference a parade led by José Nogueira de Azevedo and his friends, in which they would march in the streets, drumming, whistling, and playing the tambourines. This event took place on Carnival Monday, and José Nogueira de Azevedo encouraged everyone to join in on the festivities.

1870 was another big year in Rio Carnival history with the introduction of a concept called Cordão Carnavalesco. Cordão Carnavalesco refers to the characters people would dress up as that included kings, queens, witches, and dancers.

For the first time, people would parade according to a specific role, which coincided with the costumes they were wearing. Also in 1870 was the introduction of Cordões de Velhos, which were parade participants who donned massive paper-mâché masks, and would walk with the mannerisms of an old man.

The tradition of Corso was developed in 1907. Corso is a term referring to the inclusion of motorized vehicles in the Carnival parade along Avenue Central, now Avenue Rio Branco. Along with the motorized corsos, parade participants brought confetti and streamers — and even a spray called lança-perfume, which when inhaled gave revelers a buzz.

The tradition of Corso was developed in 1907. Corso is a term referring to the inclusion of motorized vehicles in the Carnival parade along Avenue Central, now Avenue Rio Branco. Along with the motorized corsos, parade participants brought confetti and streamers — and even a spray called lança-perfume, which when inhaled gave revelers a buzz.

According to historians, by the 1930’s this parade became widespread and popular that nearly every car owner in Rio took part in the parade. Over time, the Corsos of the past developed into the massive and elaborately decorated floats that you will find at Carnival today.

In the 1872, a bahian immigrant to Rio de Janeiro named Hilário Jovino da Silva developed a new form of parade called Ranchos Carnavalescos. Not gaining traction until 1911, these parades, orchestras comprised of strings (ganzás), flutes, drums, and other instruments, accompanied the costumed Carnival participants as they made their way down the various parade routes, adding an entirely new element to Carnival that lives on in the Rio Carnival Street Parades.

Both the inclusion of themed characters with specific roles and responsibilities, in addition to the rhythm and beats added by the orchestras, played an important part to the evolution of Carnival as a competition. But it wasn’t until the brewery Hanseática decided to sponsor the event did organized competitions officially form.

Organized competitions quickly became a favorite event of Carnival in Rio. By this point many of the elements of  today’s Rio Carnival Sambadrome Parades had already developed — such as a first-wing (abre alas), the orchestra, a male choir, and a female choir, in addition to a couple comprised of a mestre sala and a porta bandeira.

today’s Rio Carnival Sambadrome Parades had already developed — such as a first-wing (abre alas), the orchestra, a male choir, and a female choir, in addition to a couple comprised of a mestre sala and a porta bandeira.

There has been a Carnival festival in Brazil and in Rio de Janeiro for centuries, but Samba Schools were introduced to Rio Carnival in the 1920s, quickly adopting this formal structure for parades.

The first samba group to take part in the parades, Portela, was founded in 1923; however, since Portela was considered a group not a school, it does not hold claim to the title of the first Samba School. While Portela holds the record for the most victories of all the schools (21), the first official Samba School was called Deixar Falar.

Due to the fact that they were initially located to an academic institution, Deixar Falar, founded in 1928, was the first samba group to call themselves a Samba School, and now lays claim to that title. However, the oldest remaining Samba School is Mangueira, which was also founded in 1928.

In a ceremony dating back to 1933, the Mayor of Rio kicks off the Carnival festivities by handing an over-sized silver and gold key to the city to a man called King Momo — the “Fat King”. Once King Momo has the key is in his possession and decides to give the signal, the wild and crazy Carnival officially begins.

King Momo plays an important role throughout the events of Carnival. King Momo’s role is not just limited to the opening ceremony; he can also be seen opening balls, parades, and other celebrations throughout the course of Carnaval.

King Momo plays an important role throughout the events of Carnival. King Momo’s role is not just limited to the opening ceremony; he can also be seen opening balls, parades, and other celebrations throughout the course of Carnaval.

But the “Fat King” does not only open events. He is also responsible for both setting and maintaining the right Carnival atmosphere. He gets the party started and keeps the party going. From the moment Carnival is underway, King Momo does everything in his power to keep the city in a constant state of revelry. In other words, when King Momo dances, you dance!

The origins of King Momo comes from a combination of Greek mythology and Brazilian folklore. As the legend goes, the robust King Momo is a mythological Greek god of mockery and excess who was booted from Mount Olympus and lived as an exile in Rio.

Soon thereafter, the world underwent a period of change and fighting. When World War II broke out, the city of Rio decided to temporarily suspend the Carnival Parade. Festivities did not resume until 1947, two years after the end of the war.

From the early days of Carnival, centuries ago, the streets of Rio served as the primary and most important stage of the event; most notable among them is President Vargas Avenue. Over time it has developed into one of the biggest and most spectacular events in the world. For this reason the government decided that Carnival deserved its own home, and commissioned world-renowned architect Oscar Niemeyer to designed the plans for the venue. In 1984 the Sambadrome was built and has remained the official venue of Rio Carnival ever since.

From the early days of Carnival, centuries ago, the streets of Rio served as the primary and most important stage of the event; most notable among them is President Vargas Avenue. Over time it has developed into one of the biggest and most spectacular events in the world. For this reason the government decided that Carnival deserved its own home, and commissioned world-renowned architect Oscar Niemeyer to designed the plans for the venue. In 1984 the Sambadrome was built and has remained the official venue of Rio Carnival ever since.

Also available in: Portuguese (Brazil)

English

English  Português

Português